BASIC INFO OF MONTENEGRO

BASIC INFO ON MONTENEGRO

On the 21st of May 2006, after 88 years as part of Yugoslavia, Montenegro reappeared on the map of Europe, in the club of independent nations which it joined for the first time in 1878. Although national and tourist promotion portray it as a Mediterranean land, the landscape resembles much more the etymology of its name, Crna Gora (in Italian Montagna Nera), translated in English as the Black Mountain, and indeed, it is high mountains that occupy more than three-quarters of the territory. Until a few years ago, the country’s beautiful Adriatic coast was the hidden gem of the Mediterranean, but its sandy coves and pretty fishing villages are becoming once again the playground for tourists from all around the world. The rugged scenery of the interior, the craggy peaks of the Dinaric Alps, and the deep canyons and broad plateaus between them are a delight for adventurers ready to explore some of the least-known, yet most beautiful corners of Europe. Although counted as one of the smallest countries in Europe, Montenegro displays remarkable geographic diversity.

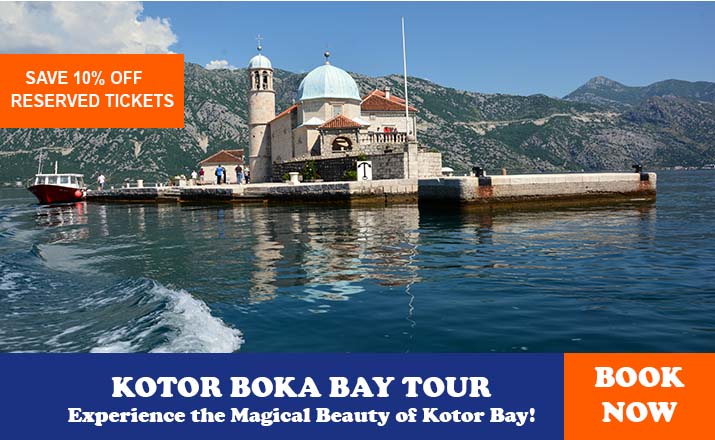

Beguiling seascapes with tall mountains looming over the gentile beaches characterize most of the coastland, but it is Boka Kotorska (the Gulf of Kotor) with its fjord-like appearance and medieval township Kotor that represents its most distinguishing feature. In the central region, mountains for a moment yield to the flat and fertile plain in which lies the nation’s capital, Podgorica, and the nearby Skadarsko Lake, a marshy bird sanctuary with villages of stone houses scattered along its coast. The north and the east seem lost in the endless lines of mountains, carved with deep canyons, amongst them that of the River Tara, the second deepest in the world.

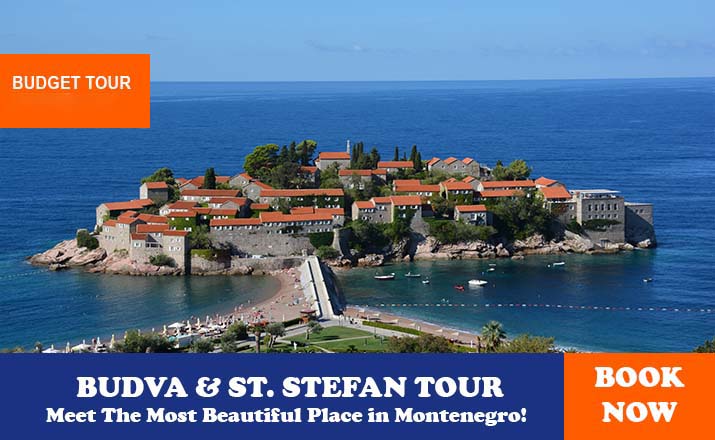

Montenegro is changing rapidly, and the contrasts of old and new will all the times bewilder the visitors. In the backwater rural communities far from major roads, people stick to the traditional sheep and cattle breeding, as well as the notions of stoic bravery, which were forged by the centuries-long resistance of the Turks. On the other hand, fashionable coast resorts such as Sveti Stefan, the raving Budva, or the posh restaurants in Podgorica embody the other face of this fast-changing nation.

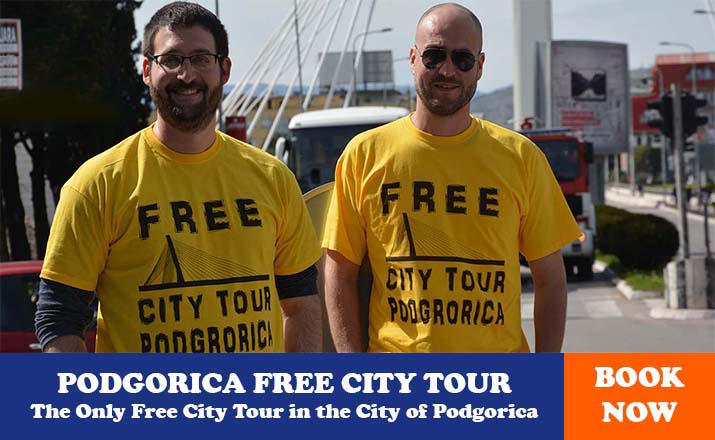

Montenegro Hostel Team

SOCIETY

SOCIETY

To a foreign observer, the population of Montenegro might seem homogeneous. The harsh struggle for survival in their high mountains and fights against the Turks and other conquerors gave birth to very tall, strong people. The same homogeneity is seen in the language, with 95% of the people speaking the Montenegrin language, a branch of the South-Slavic language, which is also spoken in Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Croatia, like the Serbian, Bosnian, and Croatian languages.

Considering this one, you will be surprised to take a look at the ethnic composition according to the census of 2010, with Montenegrins, Serbs, Muslims, Bosniaks, Albanians, and Croats, all additionally claiming to speak their language. This dazzling diversity stems from the bloody national conflicts that raged across the area of ex-Yugoslavia during the 1990s and which Montenegro managed to escape, but only narrowly. In the same period, the traditional Orthodox Christian majority split into two: ethnic Montenegrins and ethnic Serbs. There is absolutely no way for an outsider to distinguish between the two, as the break was so radical that it even divided members of the same family.

The whole dispute between the two groups can be reduced to the dilemma of whether the Orthodox populace of Montenegro is Serbs by origin and tradition or whether they represent a separate ethnicity built up during Montenegro’s independent existence as a state. A similar kind of split, though much milder, is seen amongst the Slavic-speaking Muslims, where older people in remote villages still cling to the old pattern of “Muslims from Montenegro”, while the younger and urban communities prefer being called Bosniaks, underlining their unity with the Muslim population of the neighboring Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Croats speak the same language as the previous groups but are Roman Catholics and are concentrated in the maritime region, which was long under the rule of Venice and Austria. Ethnic Albanians living in Montenegro have a different language from the rest of the populace, but adhere to two religions. The majority is Muslim, while some are Catholic. Though this ethnic mishmash, which is still bubbling in its creation, causes many disputes, like the one regarding the name of the official language (changed from Serbian to Montenegrin in 2007), all of the ethnic and religious groups enjoy broad rights, while the situation in which no group has an absolute majority may be the Montenegrin way towards a civic society.

One more confusing element in Montenegrin society is the two official scripts, Cyrillic and Latin, which are equally used. Except in the littoral, Latin letters were virtually unknown in the rest of the country until the Yugoslav unification (1918). Gradually, the Latin script penetrated deeper and is nowadays used more often than the traditional Cyrillic script. The Cyrillic alphabet used in Montenegro is the same as the alphabet used in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia, as well as in Croatia among ethnic Serbs. It differs in many ways from the Cyrillic alphabet used in Greek, Bulgarian, and Russian languages.

Montenegro Hostel Team

ECONOMY AND TOURISM

ECONOMY AND TOURISM IN MONTENEGRO

During the communist era (1944-1990), the country’s economy was radically shifted from agriculture to heavy industry. However, the international economic sanctions imposed on Montenegro in the 1900s suffocated most of the state-held enterprises, which were later either bought by rich businessmen or are still barely functioning and expecting reorganization. Important industries include the aluminum plants in Podgorica, a steel plant in Nikšić, the coal mines of Pljevlja, and power generators from hydro and coal plants. These are joined by the export of raw wood and wood processing which continue to shrink in the surface of land under forests, which are roughly the amount to roughly half of the total area.

Agriculture, with animal husbandry in the interior and olive growing and fishing along the coast, has been reduced to, at best, production for the local markets. The only substantial exporter in the field is “Plantaže”, a company whose 15 million bottles of excellent wine per year are produced from huge vine plantations south of Podgorica. Fully aware of the situation as well as Montenegro’s huge potential, the government has wisely listed tourism as one of its priorities. A clever marketing campaign, foreign investments, and improvements in the country’s infrastructure have managed to increase the number of tourists to grow every year.

Still, there is a lot of work to be done, one of the problems being that the Montenegrin Adriatic coast, where the large majority of tourists go, is in high summer often has traffic jams along its roads. On the other hand, the rural north and east of the country, with their magnificent mountains, are still visited by a smaller portion of the guests. The other boom is recorded in the real estate business.

The first wave of trading hit the coast in 2005 with smaller plots, and old new houses as well as whole swathes of land being mostly bought by the Russians, British, and Irish. Tourism and the rise of real estate values significantly increased the country’s GDP, though Montenegro, on the whole, can be quite satisfied with its development after its independence in 2006.

Montenegro Hostel Team

WAY OF LIFE

WAY OF LIFE in Montenegro

In only a century, Montenegro underwent a huge transformation from a land of peasants always ready to reach for their swords and make war against the Turks to a land of services and tourism, with almost 70% of people living in towns. Though the stereotypical Montenegrin is still portrayed in cartoon strips and caricatures as a splendidly mustached chap with a shallow Montenegrin cap on his head, you will be lucky to meet men like this only in the most remote areas, as the national costume is out of use for decades and is now only seen in folklore manifestations, special occasions, and souvenir shops.

While the decades of fast development under communism have wiped out many other forms of traditional behavior, the economic depression of the 1990s and the recent rather uncontrolled progress have introduced the bad aspects of capitalism and consumerism into everyday life. Today, middle-aged Montenegrins from the towns are to be seen drinking espresso in street cafes at noon, boisterously waving around with their new mobile phones and car keys. Owing to such a car also means reckless, high-speed driving along the curvy roads with little respect for anything but one’s haste, a typical sight on the Montenegrin roads. Many of the young don’t have anything against this type of image, but there is also a rising population of fully European-minded and mannered youths living a life similar to those people their age in the West.

In contrast to the habits of the middle-aged and young, the older generations still hold to such pastimes as creating huge family trees (deriving from the old oral tradition of remembering fore-fathers up to 20 or more generations back), collecting data on their family, brotherhood, and clan, reciting verses of the national-poet Njegoš, or even playing the gusle (one-string instrument). All those quite traditional activities are now clad in more modern forms.

One thing that's certain about Montenegro is that it is a very small society in which it is next to impossible not to know almost all of the people your age in your town, and most of them with interests similar to yours in the whole country. Adding that family ties are often overbearing, this often leads to migration towards the larger towns or abroad. Many, however, leave the country for purely financial reasons, and these factors combined caused Montenegrins to scatter all over Europe, North America, and Australia.

Montenegro Hostel Team